As Latinx Heritage month draws to a close, I find myself reflecting on my people. As BRIC delves deeper into using Critical Race Theory as a strategy to enrich our stakeholder and community engagement process, we are learning a lot.

First and foremost, BRIC is a community of learners and we are leveraging that more than ever in this moment. Our work with Dr. Amara Pérez has introduced us to an exercise she learned in her work with the organization Southerners on New Ground (SONG) entitled, “My People”. In this exercise, participants are welcomed into a meeting by presenting their “people” to the rest of the group. The descriptions an individual’s uses to define their people vary widely and are really meant to introduce others to their different identities, drawing upon as many perspectives as possible.

Beyond thinking about how my own people are space geeks and seekers of justice, I was drawn to memories about my Guatemalan family’s history and upbringing. My people are immigrants, proud Americans, givers, hard workers, and life-long learners. My people are loud, joyful, tired, and anxious about where we find ourselves in our country.

This month, more than any other, I am reflecting on my heritage and its intersection with the field of architecture. Growing up, I didn’t know anyone who was an architect – other than Mike Brady of the Brady Bunch. My dad was an electrical engineer, but the concept of being a designer and shaping the built environment was one that was foreign to me. Sadly, my experience was not unique; almost every BIPOC designer I know says the same thing. Representation matters and it matters most when we are trying to address underrepresented and marginalized people in the architecture industry.

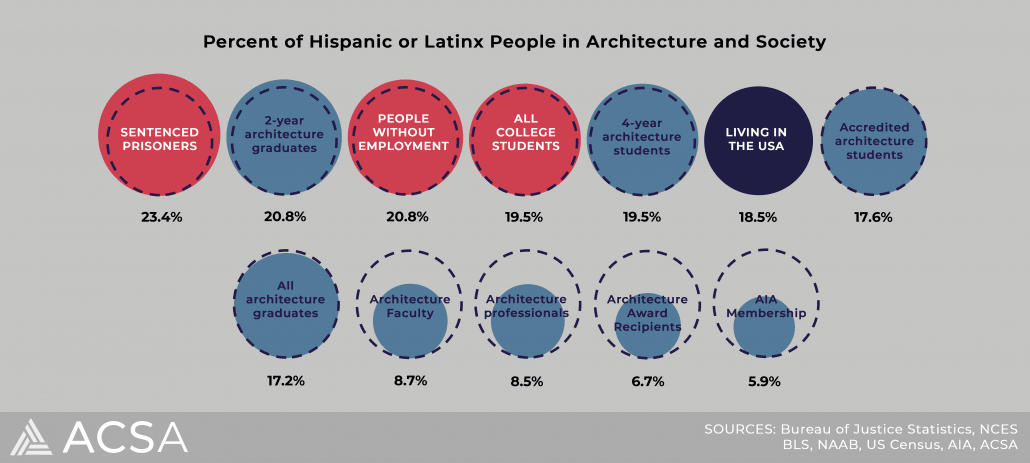

Unsurprisingly, my peers’ experiences echo national statistics. According to the Association of Collegiate Schools of Architecture, Hispanic or Latinx people are almost three times as likely to be in prison as they are to be architectural professionals. Click here for more info.

Specifically, the delta between the percentage of Hispanic or Latinx people who enter architecture schools (19.5%) and those who become licensed architects (8.5%) is also one we need to look at more deeply. Despite the fact that they consistently complete their education and examination sooner than their peers, Latina/x individuals in 2019 represented less than 1% of ARE completion to licensure, according to NOMAS_NCSU and NCARB’s demographics study. Unfortunately, 68% of those same folx agree they were less likely to receive experience opportunities.

So, how do we change the future to shape it into the more equitable, just, and humane world we want to see? This question has driven our leadership team’s work for months and the solutions are hard. BRIC’s leaders acknowledge that this will not be a sprint, but rather a marathon.

Building up the pipeline of BIPOC youth interested in architecture is a start. We need to be in schools where BIPOC kids – girls, especially – can be introduced to architecture and design as a viable profession. We need to work alongside programs like ACE Mentors, Architects in School, WildX Project, and Your Street Your Voice to continue to encourage, mentor, and guide BIPOC youth towards careers in architecture. We need to create specifically targeted scholarships to help BIPOC architecture students through school and then hire them as interns and employees. Together, we will use our collective experiences to design opportunities and learning environments that will inspire future generations to reach their highest potential. #SiSePuede